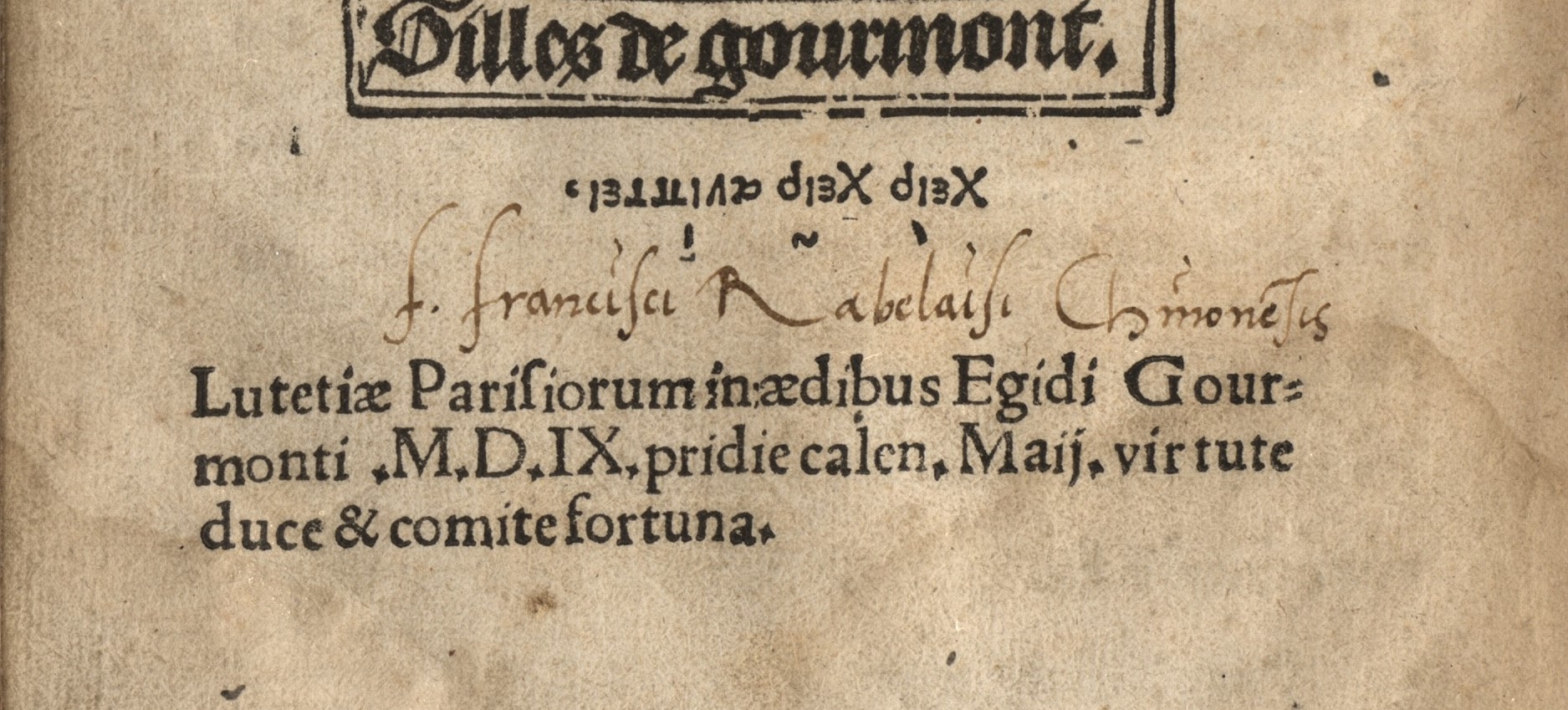

“Brother François Rabelais, of Chinon”

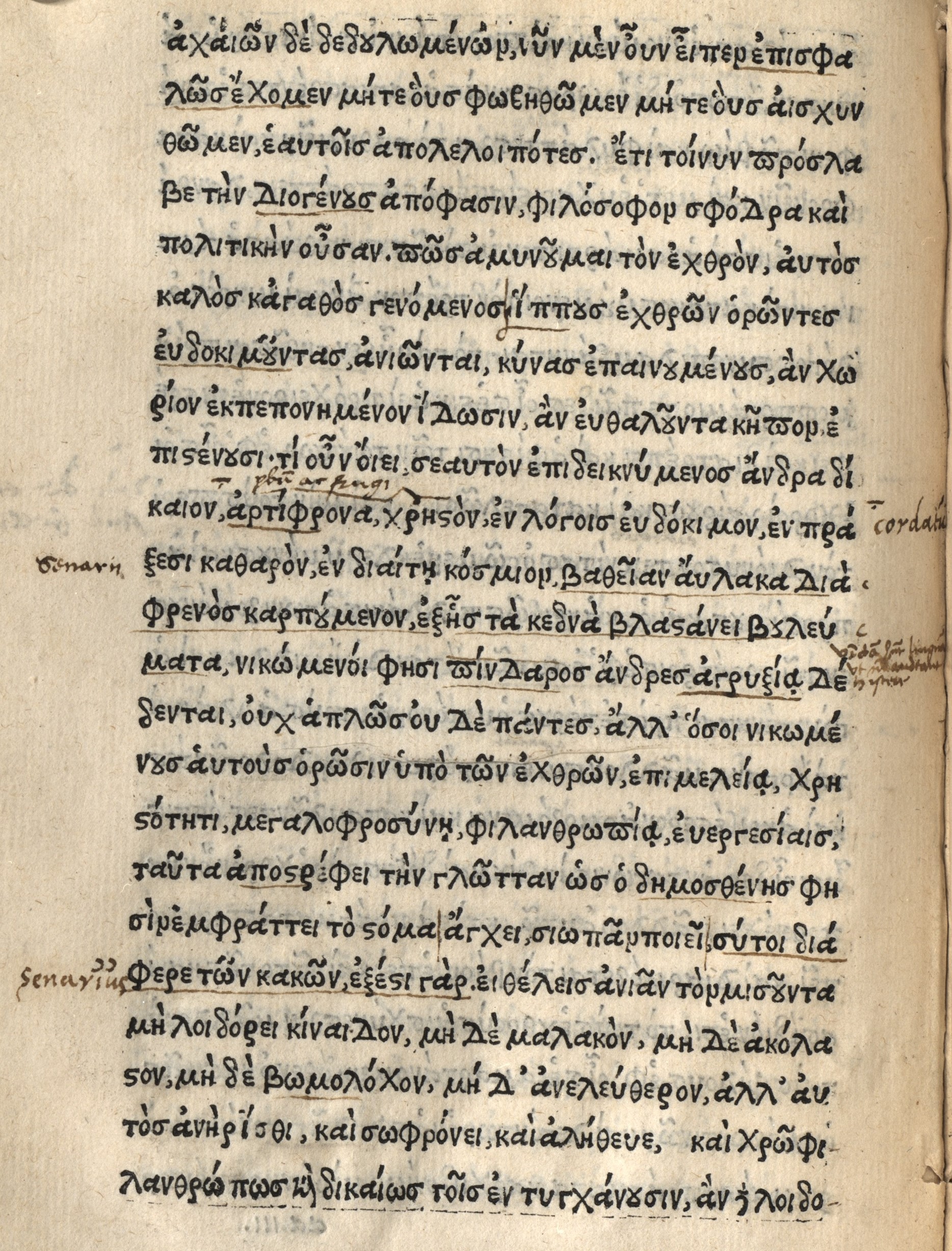

Rabelais’ library was voluminous; it was, however, separated and dispersed. There are at least thirty titles dotted across Europe and the United States, bearing the signature of Pantagruel’s author. The volume held in Martin Bodmer’s collection contains the Sphaera of Pseudo-Proclus, Theocritus’ Idylls, several of Plutarch’s Moral Works and Hesiod’s Works and Days. “Brother François Rabelais, of Chinon”: Rabelais would have added his signature around 1520, making the book the oldest instance of his handwriting. By this fact alone, the piece carries superlative importance, making it possible to read Greek over the shoulders of young François, Franciscan brother at the friary of Fontenay-le-Comte.

Using this anthology of short texts, Rabelais learned Greek in Poitou. We can imagine him at his study table, and at his side the aptly-named Pierre Lamy, Petrus Amicus, a novice ahead of François in years and especially in his knowledge of Plato’s language. Henri Busson called them the Dioscuri of Fontenay-le-Comte: Lamy et Rabelais, the Castor and Pollux of Hellenism in a little Poitou friary!

This learned brotherhood provoked a negative response and the Greek books were confiscated by the superiors of the friary. In those days, Greek was considered dubious, the language of suspected heresy ever since Erasmus had suggested a return to the original text of the New Testament, in direct opposition to a tradition that had always blindly followed the Latin Vulgate. For our Dioscuri, it took the intervention of the great Gillaume Budé, star of the French humanists, for the Greek books to be returned. Rabelais would recount this episode slyly in the Tiers livre (1546), when he tells of Pierre Lamy attempting to escape the elves.

Was the anthology held by the Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, this collection of texts published with the first Greek characters available in Paris around 1510, among the books confiscated at Fontenay? Perhaps. At the very least, it attests to the young Franciscan’s passion for learning Greek, the “language without which one could not seriously say he is a savant,” as Gargantua would say to his son. Goethe, Weltliteratur personified, would say this very thing to Eckermann: “In our need for exemplary works, we must always go back to the Ancient Greeks.” Rabelais would have hardly needed to read this declaration before signing his own name.